Open Source undefined, part 1: the alternative origin story

What is the definition of “Open Source”?

There’s been no shortage of contention on what “Open Source software” means. Two instances that stand out to me personally are ElasticSearch’s “Doubling down on Open” and Scott Chacon’s “public on GitHub”.

I’ve been active in Open Source for 20 years and could use a refresher on its origins and officialisms. The plan was simple: write a blog post about why the OSI (Open Source Initiative) and its OSD (Open Source Definition) are authoritative, collect evidence in its support (confirmation that they invented the term, of widespread acceptance with little dissent, and of the OSD being a practical, well functioning tool). That’s what I keep hearing, I just wanted to back it up. Since contention always seems to be around commercial re-distribution restrictions (which are forbidden by the OSD), I wanted to particularly confirm that there hasn’t been all that many commercial vendors who’ve used, or wanted, to use the term “open source” to mean “you can view/modify/use the source, but you are limited in your ability to re-sell, or need to buy additional licenses for use in a business”

However, the further I looked, the more I found evidence of the opposite of all of the above. I’ve spent a few weeks now digging and some of my long standing beliefs are shattered. I can’t believe some of the things I found out. Clearly I was too emotionally invested, but after a few weeks of thinking, I think I can put things in perspective. So this will become not one, but multiple posts.

The goal for the series is look at the tensions in the community/industry (in particular those directed towards the OSD), and figure out how to resolve, or at least reduce them.

Without further ado, let’s get into the beginnings of Open Source.

The “official” OSI story.

Let’s first get the official story out the way, the one you see repeated over and over on websites, on Wikipedia and probably in most computing history books.

Back in 1998, there was a small group of folks who felt that the verbiage at the time (Free Software) had become too politicized. (note: the Free Software Foundation was founded 13 years prior, in 1985, and informal use of “free software” had around since the 1970’s). They felt they needed a new word “to market the free software concept to people who wore ties”. (source) (somewhat ironic since today many of us like to say “Open Source is not a business model”)

Bruce Perens - an early Debian project leader and hacker on free software projects such as busybox - had authored the first Debian Free Software Guidelines in 1997 which was turned into the first Open Source Definition when he founded the OSI (Open Source Initiative) with Eric Raymond in 1998. As you continue reading, keep in mind that from the get-go, OSI’s mission was supporting the industry. Not the community of hobbyists.

Eric Raymond is of course known for his seminal 1999 essay on development models “The cathedral and the bazaar”, but he also worked on fetchmail among others.

According to Bruce Perens, there was some criticism at the time, but only to the term “Open” in general and to “Open Source” only in a completely different industry.

At the time of its conception there was much criticism for the Open Source campaign, even among the Linux contingent who had already bought-in to the free software concept. Many pointed to the existing use of the term “Open Source” in the political intelligence industry. Others felt the term “Open” was already overused. Many simply preferred the established name Free Software. I contended that the overuse of “Open” could never be as bad as the dual meaning of “Free” in the English language–either liberty or price, with price being the most oft-used meaning in the commercial world of computers and software

From Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution: The Open Source Definition

Furthermore, from Bruce Perens’ own account:

I wrote an announcement of Open Source which was published on February 9 [1998], and that’s when the world first heard about Open Source.

source: On Usage of The Phrase “Open Source”

Occasionally it comes up that it may have been Christine Peterson who coined the term earlier that week in February but didn’t give it a precise meaning. That was a task for Eric and Bruce in followup meetings over the next few days.

Even when you’re the first to use or define a term, you can’t legally control how others use it, until you obtain a Trademark. Luckily for OSI, US trademark law recognizes the first user when you file an application, so they filed for a trademark right away. But what happened? It was rejected! The OSI’s official explanation reads:

We have discovered that there is virtually no chance that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office would register the mark “open source”; the mark is too descriptive. Ironically, we were partly a victim of our own success in bringing the “open source” concept into the mainstream

This is our first 🚩 red flag and it lies at the basis of some of the conflicts which we will explore in this, and future posts. (tip: I found this handy Trademark search website in the process)

Regardless, since 1998, the OSI has vastly grown its scope of influence (more on that in future posts), with the Open Source Definition mostly unaltered for 25 years, and having been widely used in the industry.

Prior uses of the term “Open Source”

Many publications simply repeat the idea that OSI came up with the term, has the authority (if not legal, at least in practice) and call it a day. I, however, had nothing better to do, so I decided to spend a few days (which turned into a few weeks 😬) and see if I could dig up any references to “Open Source” predating OSI’s definition in 1998, especially ones with different meanings or definitions.

Of course, it’s totally possible that multiple people come up with the same term independently and I don’t actually care so much about “who was first”, I’m more interested in figuring out what different meanings have been assigned to the term and how widespread those are.

In particular, because most contention is around commercial limitations (non-competes) where receivers of the code are forbidden to resell it, this clause of the OSD stands out:

Free Redistribution: The license shall not restrict any party from selling (…)

Turns out, the “Open Source” was already in use for more than a decade, prior to the OSI founding.

OpenSource.com

In 1998, a business in Texas called “OpenSource, Inc” launched their website. They were a “Systems Consulting and Integration Services company providing high quality, value-added IT professional services”. Sometime during the year 2000, the website became a RedHat property. Enter the domain name on Icann and it reveals the domain name was registered Jan 8, 1998. A month before the term was “invented” by Christine/Richard/Bruce. What a coincidence. We are just warming up…

Caldera announces Open Source OpenDOS

In 1996, a company called Caldera had “open sourced” a DOS operating system called OpenDos. Their announcement (accessible on google groups and a mailing list archive) reads:

Caldera Announces Open Source for DOS.

(…)

Caldera plans to openly distribute the source code for all of the DOS technologies it acquired from Novell., Inc

(…)

Caldera believes an open source code model benefits the industry in many ways.

(…)

Individuals can use OpenDOS source for personal use at no cost.

Individuals and organizations desiring to commercially redistribute

Caldera OpenDOS must acquire a license with an associated small fee.

Today we would refer to it as dual-licensing, using Source Available due to the non-compete clause. But in 1996, actual practitioners referred to it as “Open Source” and OSI couldn’t contest it because it didn’t exist!

You can download the OpenDos package from ArchiveOS and have a look at the license file, which includes even more restrictions such as “single computer”. (like I said, I had nothing better to do).

Investigations by Martin Espinoza re: Caldera

On his blog, Martin has an article making a similar observation about Caldera’s prior use of “open source”, following up with another article which includes a response from Lyle Ball, who headed the PR department of Caldera

Quoting Martin:

As a member of the OSI, he [Bruce] frequently championed that organization’s prerogative to define what “Open Source” means, on the basis that they invented the term. But I [Martin] knew from personal experience that they did not. I was personally using the term with people I knew before then, and it had a meaning — you can get the source code. It didn’t imply anything at all about redistribution.

The response from Caldera includes such gems as:

I joined Caldera in November of 1995, and we certainly used “open source” broadly at that time. We were building software. I can’t imagine a world where we did not use the specific phrase “open source software”. And we were not alone. The term “Open Source” was used broadly by Linus Torvalds (who at the time was a student (…), John “Mad Dog” Hall who was a major voice in the community (he worked at COMPAQ at the time), and many, many others.

Our mission was first to promote “open source”, Linus Torvalds, Linux, and the open source community at large. (…) we flew around the world to promote open source, Linus and the Linux community….we specifically taught the analysts houses (i.e. Gartner, Forrester) and media outlets (in all major markets and languages in North America, Europe and Asia.) (…) My team and I also created the first unified gatherings of vendors attempting to monetize open source

So according to Caldera, “open source” was a phenomenon in the industry already and Linus himself had used the term. He mentions plenty of avenues for further research, I pursued one of them below.

Linux Kernel discussions

Mr. Ball’s mentions of Linus and Linux piqued my interest, so I started digging.

I couldn’t find a mention of “open source” in the Linux Kernel Mailing List archives prior to the OSD day (Feb 1998), though the archives only start as of March 1996. I asked ChatGPT where people used to discuss Linux kernel development prior to that, and it suggested 5 Usenet groups, which google still lets you search through:

- alt.os.linux (no hits)

- comp.os.minix (no hits)

- comp.os.linux (one hit!)

- comp.os.linux.development (no hits)

- comp.os.linux.announce (two hits!)

What were the hits? Glad you asked!

comp.os.linux: a 1993 discussion about supporting binary-only software on Linux

This conversation predates the OSI by five whole years and leaves very little to the imagination:

The GPL and the open source code have made Linux the success that it is. Cygnus and other commercial interests are quite comfortable with this open paradigm, and in fact prosper. One need only pull the source code to GCC and read the list of many commercial contributors to realize this.

comp.os.linux.announce: 1996 announcement of Caldera’s open-source environment

In November 1996 Caldera shows up again, this time with a Linux based “open-source” environment:

Channel Partners can utilize Caldera’s Linux-based, open-source environment to remotely manage Windows 3.1 applications at home, in the office or on the road. By using Caldera’s OpenLinux (COL) and Wabi solution, resellers can increase sales and service revenues by leveraging the rapidly expanding telecommuter/home office market. Channel Partners who create customized turn-key solutions based on environments like SCO OpenServer 5 or Windows NT,

comp.os.linux.announce: 1996 announcement of a trade show

On 17 Oct 1996 we find this announcement

There will be a Open Systems World/FedUnix conference/trade show in Washington DC on November 4-8. It is a traditional event devoted to open computing (read: Unix), attended mostly by government and commercial Information Systems types.

In particular, this talk stands out to me:

** Schedule of Linux talks, OSW/FedUnix'96, Thursday, November 7, 1996 ***

(…)

11:45 Alexander O. Yuriev, “Security in an open source system: Linux study”

The context here seems to be open standards, and maybe also the open source development model.

1990: Tony Patti on “software developed from open source material”

in 1990, a magazine editor by name of Tony Patti not only refers to Open Source software but mentions that NSA in 1987 referred to “software was developed from open source material”

1995: open-source changes emails on OpenBSD-misc email list

I could find one mention of “Open-source” on an OpenBSD email list, seems there was a directory “open-source-changes” which had incoming patches, distributed over email. (source). Though perhaps the way to interpret is, to say it concerns “source-changes” to OpenBSD, paraphrased to “open”, so let’s not count this one.

(I did not look at other BSD’s)

Bryan Lunduke’s research

Bryan Lunduke has done similar research and found several more USENET posts about “open source”, clearly in the context of of source software, predating OSI by many years. He breaks it down on his substack. Some interesting examples he found:

19 August, 1993 post to comp.os.ms-windows

Anyone else into “Source Code for NT”? The tools and stuff I’m writing for NT will be released with source. If there are “proprietary” tricks that MS wants to hide, the only way to subvert their hoarding is to post source that illuminates (and I don’t mean disclosing stuff obtained by a non-disclosure agreement).

(source)

Then he writes:

Open Source is best for everyone in the long run.

Written as a matter-of-fact generalization to the whole community, implying the term is well understood.

December 4, 1990

BSD’s open source policy meant that user developed software could be ported among platforms, which meant their customers saw a much more cost effective, leading edge capability combined hardware and software platform.

1985: The “the computer chronicles documentary” about UNIX.

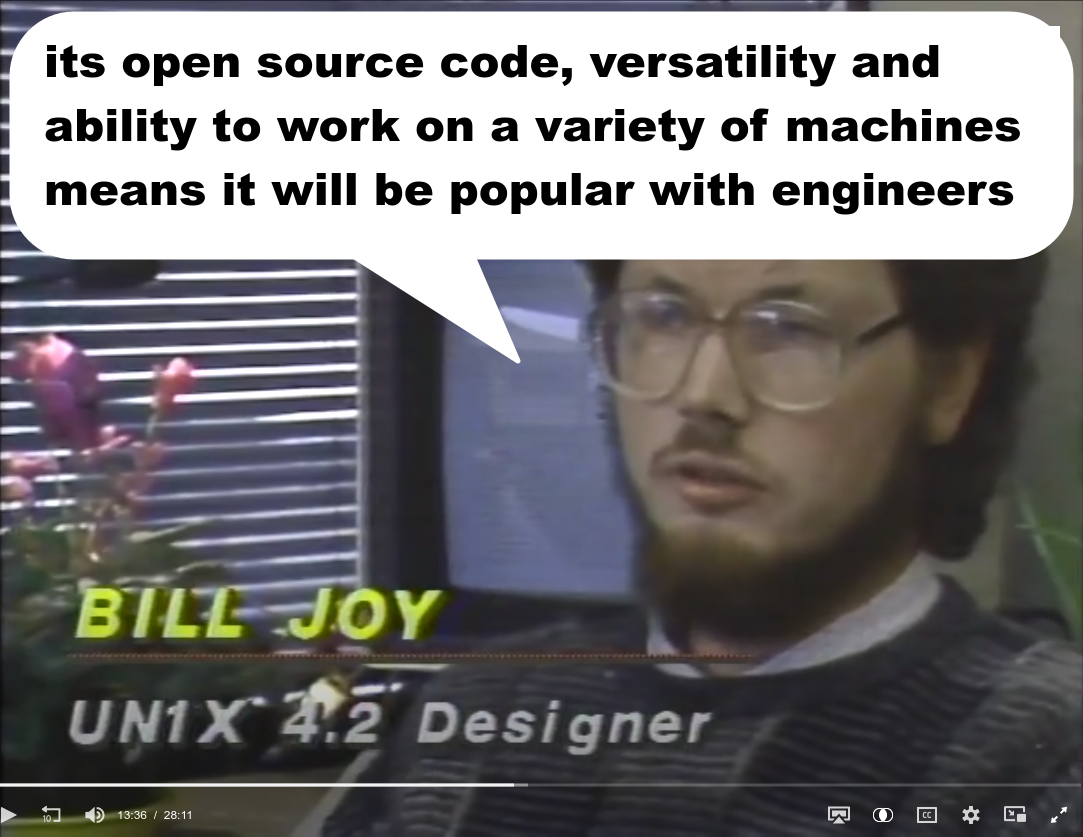

The Computer Chronicles was a TV documentary series talking about computer technology, it started as a local broadcast, but in 1983 became a national series. On February 1985, they broadcasted an episode about UNIX. You can watch the entire 28 min episode on archive.org, and it’s an interesting snapshot in time, when UNIX was coming out of its shell and competing with MS-DOS with its multi-user and concurrent multi-tasking features. It contains a segment in which Bill Joy, co-founder of Sun Microsystems is being interviewed about Berkley Unix 4.2. Sun had more than 1000 staff members. And now its CTO was on national TV in the United States. This was a big deal, with a big audience. At 13:50 min, the interviewer quotes Bill:

“He [Bill Joy] says its open source code, versatility and ability to work on a variety of machines means it will be popular with scientists and engineers for some time”

“Open Source” on national TV. 13 years before the founding of OSI.

Uses of the word “open”

We’re specifically talking about “open source” in this article. But we should probably also consider how the term “open” was used in software, as they are related, and that may have played a role in the rejection of the trademark.

Well, the Open Software Foundation launched in 1988. (10 years before the OSI). Their goal was to make an open standard for UNIX. The word “open” is also used in software, e.g. Common Open Software Environment in 1993 (standardized software for UNIX), OpenVMS in 1992 (renaming of VAX/VMS as an indication of its support of open systems industry standards such as POSIX and Unix compatibility), OpenStep in 1994 and of course in 1996, the OpenBSD project started. They have this to say about their name: (while OpenBSD started in 1996, this quote is from 2006):

The word “open” in the name OpenBSD refers to the availability of the operating system source code on the Internet, although the word “open” in the name OpenSSH means “OpenBSD”. It also refers to the wide range of hardware platforms the system supports.

Does it run DOOM?

The proof of any hardware platform is always whether it can run Doom. Since the DOOM source code was published in December 1997, I thought it would be fun if ID Software would happen to use the term “Open Source” at that time. There are some FTP mirrors where you can still see the files with the original December 1997 timestamps (e.g. this one). However, after sifting through the README and other documentation files, I only found references to the “Doom source code”. No mention of Open Source.

The origins of the famous “Open Source” trademark application: SPI, not OSI

This is not directly relevant, but may provide useful context: In June 1997 the SPI (“Software In the Public Interest”) organization was born to support the Debian project, funded by its community, although it grew in scope to help many more free software / open source projects. It looks like Bruce, as as representative of SPI, started the “Open Source” trademark proceedings. (and may have paid for it himself). But then something happened, 3/4 of the SPI board (including Bruce) left and founded the OSI, which Bruce announced along with a note that the trademark would move from SPI to OSI as well. Ian Jackson - Debian Project Leader and SPI president - expressed his “grave doubts” and lack of trust. SPI later confirmed they owned the trademark (application) and would not let any OSI members take it. The perspective of Debian developer Ean Schuessler provides more context.

A few years later, it seems wounds were healing, with Bruce re-applying to SPI, Ean making amends, and Bruce taking the blame.

All the bickering over the Trademark was ultimately pointless, since it didn’t go through.

Searching for SPI on the OSI website reveals no acknowledgment of SPI’s role in the story. You only find mentions in board meeting notes (ironically, they’re all requests to SPI to hand over domains or to share some software).

By the way, in November 1998, this is what SPI’s open source web page had to say:

Open Source software is software whose source code is freely available

A Trademark that was never meant to be.

Lawyer Kyle E. Mitchell knows how to write engaging blog posts. Here is one where he digs further into the topic of trademarking and why “open source” is one of the worst possible terms to try to trademark (in comparison to, say, Apple computers).

He writes:

At the bottom of the hierarchy, we have “descriptive” marks. These amount to little more than commonly understood statements about goods or services. As a general rule, trademark law does not enable private interests to seize bits of the English language, weaponize them as exclusive property, and sue others who quite naturally use the same words in the same way to describe their own products and services.

(…)

Christine Peterson, who suggested “open source” (…) ran the idea past a friend in marketing, who warned her that “open” was already vague, overused, and cliche.

(…)

The phrase “open source” is woefully descriptive for software whose source is open, for common meanings of “open” and “source”, blurry as common meanings may be and often are.

(…)

no person and no organization owns the phrase “open source” as we know it. No such legal shadow hangs over its use. It remains a meme, and maybe a movement, or many movements. Our right to speak the term freely, and to argue for our own meanings, understandings, and aspirations, isn’t impinged by anyone’s private property.

So, we have here a great example of the Trademark system working exactly as intended, doing the right thing in the service of the people: not giving away unique rights to common words, rights that were demonstrably never OSI’s to have.

I can’t decide which is more wild: OSI’s audacious outcries for the whole world to forget about the trademark failure and trust their “pinky promise” right to authority over a common term, or the fact that so much of the global community actually fell for it and repeated a misguided narrative without much further thought. (myself included)

I think many of us, through our desire to be part of a movement with a positive, fulfilling mission, were too easily swept away by OSI’s origin tale.

Co-opting a term

OSI was never relevant as an organization and hijacked a movement that was well underway without them.

(source: a harsh but astute Slashdot comment)

We have plentiful evidence that “Open Source” was used for at least a decade prior to OSI existing, in the industry, in the community, and possibly in government. You saw it at trade shows, in various newsgroups around Linux and Windows programming, and on national TV in the United States. The word was often uttered without any further explanation, implying it was a known term. For a movement that happened largely offline in the eighties and nineties, it seems likely there were many more examples that we can’t access today.

“Who was first?” is interesting, but more relevant is “what did it mean?”. Many of these uses were fairly informal and/or didn’t consider re-distribution. We saw these meanings:

- a collaborative development model

- portability across hardware platforms, open standards

- disclosing (making available) of source code, sometimes with commercial limitations (e.g. per-seat licensing) or restrictions (e.g. non-compete)

- possibly a buzz-word in the TV documentary

Then came the OSD which gave the term a very different, and much more strict meaning, than what was already in use for 15 years. However, the OSD was refined, “legal-aware” and the starting point for an attempt at global consensus and wider industry adoption, so we are far from finished with our analysis.

(ironically, it never quite matched with free software either - see this e-mail or this article)

Legend has it…

Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth

Yet, the OSI still promotes their story around being first to use the term “Open Source”. RedHat’s article still claims the same. I could not find evidence of resolution. I hope I just missed it (please let me know!). What I did find, is one request for clarification remaining unaddressed and another handled in a questionable way, to put it lightly. Expand all the comments in the thread and see for yourself For an organization all about “open”, this seems especially strange. Seems we have veered far away from the “We will not hide problems” motto in the Debian Social Contract.

Real achievements are much more relevant than “who was first”. Here are some suggestions for actually relevant ways the OSI could introduce itself and its mission:

- “We were successful open source practitioners and industry thought leaders”

- “In our desire to assist the burgeoning open source movement, we aimed to give it direction and create alignment around useful terminology”.

- “We launched a campaign to positively transform the industry by defining the term - which had thus far only been used loosely - precisely and popularizing it”

I think any of these would land well in the community. Instead, they are strangely obsessed with “we coined the term, therefore we decide its meaning. and anything else is “flagrant abuse”.

Is this still relevant? What comes next?

Trust takes years to build, seconds to break, and forever to repair

I’m quite an agreeable person, and until recently happily defended the Open Source Definition. Now, my trust has been tainted, but at the same time, there is beauty in knowing that healthy debate has existed since the day OSI was announced. It’s just a matter of making sense of it all, and finding healthy ways forward.

Most of the events covered here are from 25 years ago, so let’s not linger too much on it. There is still a lot to be said about adoption of Open Source in the industry (and the community), tension (and agreements!) over the definition, OSI’s campaigns around awareness and standardization and its track record of license approvals and disapprovals, challenges that have arisen (e.g. ethics, hyper clouds, and many more), some of which have resulted in alternative efforts and terms. I have some ideas for productive ways forward.

Stay tuned for more, sign up for the RSS feed and let me know what you think!

Comment below, on X or on HackerNews

@name